I. The Purposes of Imprisonment as a Form of Punishment in the United States

A. Justificatory Theories of Imprisonment

The purposes of punishment are commonly divided between the deontological—inflicting punishment for its own sake, i.e., retribution1—and the teleological or utilitarian—inflicting punishment to achieve some benefit, i.e., deterrence, incapacitation and rehabilitation.2 Restitution is also sometimes included, although some contend it is more properly characterized as a civil remedy, or that it is really just a means of promoting the other utilitarian goals.3

When discussing theories of punishment, at least four different questions may be involved. First, why punish at all? Second, whom should we punish? Third, how much punishment is appropriate? And fourth, which mode of punishment should we employ?4

The fourth question regarding the mode of punishment is related to, but analytically distinct from, the third question regarding the amount of punishment. Punishment could be inflicted by means of monetary penalties, imprisonment, exile, or physical torture, to name a few possibilities. Just as one could vary the amounts of different kinds of goods, so that a consumer would be indifferent between them (in that he would be willing to pay an equal price for any of them), one could, in theory, vary the amounts of different modes of punishment so that a criminal offender would be indifferent between them. For example, assuming one wanted to inflict X “units” of punishment, one might determine that a $5000 fine, thirty days in jail, or eight lashes with a whip all achieve an equivalent “amount” of punishment.5 Thus, deciding how much punishment to inflict does not dictate which modality of punishment is appropriate.6

As will be discussed below, although prevailing American views regarding the first three questions—why we punish, who should be punished, and how much they should be punished—have shifted over time, the primary mode of punishment employed—imprisonment—has remained virtually unchanged since the country’s early history.7 The question is, why prisons?[1]

One could offer either negative or positive justifications for using prisons. Negative justifications involve theoretical or pragmatic problems with the alternatives. For example, capital punishment is deemed too severe for most offenses. Torture would violate the constitutional prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment,8 and would likely be deemed too barbaric today regardless of the constitutional ban. And exile, given the required cooperation of other nations and the sophistication of modern transportation, would likely be difficult to enforce.9 As for monetary penalties, most criminals probably lack the means to compensate their victims, and garnishing their wages would take years to yield results. Prison is arguably justifiable in that it lacks many of these drawbacks.

But drawbacks to the alternatives do not dictate that prison—as opposed to some more creative alternative—is the best solution. We need positive justifications: a showing that incarceration serves some penological goal more effectively than other modes of punishment.

Prison cannot be justified on the ground that it better serves deterrence or retribution than other punishments. After all, any unpleasant experience—be it prison, torture, exile, etc.—will promote deterrence (because both the offender and third parties will want to avoid the unpleasantness in the future) and retribution (because any harm inflicted upon the offender “squares up” the wrong he committed). Assuming one could calibrate the amounts correctly, any mode of punishment serves these goals equally well.10

Nor is prison an effective means of promoting restitution. The work available to prison inmates does not pay the type of wages that would provide any significant compensation to a victim or his family.11

Thus, prison is justifiable only if it serves the remaining goals of incapacitation or rehabilitation. Prison undoubtedly does incapacitate, and does so more effectively than other means of punishment (except, obviously, for capital punishment, which is inappropriate for most offenses). Corporal punishment does not incapacitate at all (unless the offender is injured). Nor do monetary penalties. By contrast, an offender is usually completely incapacitated for the duration of his confinement.12

Although incarceration necessarily incapacitates, it does not necessarily rehabilitate. One cannot tell, as a theoretical matter, whether spending time in confinement will make offenders more likely, equally likely, or less likely to commit crimes upon release. The conditions of the offender’s confinement, with whom he interacts, and the activities in which he engages during his confinement, will likely impact its rehabilitative effect.13

As the next section demonstrates, however, many now see retribution, not rehabilitation, as the purpose of prisons. As a result, much attention is paid to sending more people to prison for longer periods, with little paid to whether the time they spend there is productive.

B. History of the Purposes of Imprisonment in the United States

- 1700s—1960s: The Predominance of Rehabilitation

When the penitentiary system in the United States began in the late eighteenth century, it was specifically designed for the purpose of rehabilitating the prisoner.14 With the exception of post-Civil War Southern prisons (which emphasized exploitative servitude, until the judicial decisions of the civil rights era put an end to such practices),15 rehabilitation continued to be the dominant goal of the American penitentiary system for nearly two centuries—that is, until the last several decades.

Although rehabilitation remained the goal until recently, views about how inmates were to be rehabilitated changed over time. Originally, the offender was separated from his former life and made to reflect—through isolation, work, fasting, and/or Bible study—in order to change his ways.16 But the results of solitary confinement and starvation diets were sorely disappointing,17 and as the Industrial Revolution gained steam, “vocational and academic training came to replace remorse and discipline as the princip[al] instrument for rehabilitation.”18 This was not an abandonment of rehabilitation as a goal, but rather a shift in approach regarding how to achieve it.

By the 1960s, a growing optimism about science in general, and psychiatry in particular, led some to view criminal behavior as a manifestation of mental illness that, with proper supervision within the criminal justice system, could be “cured.”19 Indeterminate sentencing was widespread, and parole boards were effectively given the role of determining when a prisoner was “cured” and thus fit to be released.20 This was, effectively, a medical model of criminal justice.

- The 1960s and Beyond: The Transition to Retribution and Incapacitation

The medical model—and the rehabilitative model in general—came under increasing attack in the late 1960s and 1970s, from both the right and the left.21 First, there was a concern that, because the medical model is deterministic, explaining all behavior without regard to the individual’s will, it threatened to undermine notions of moral accountability at the heart of criminal law.22 Second, some believed that the medical model operated to the detriment of the “patient:” the prisoner ran the risk that he would never be found “cured” and remain incarcerated indefinitely.23 Third, the assumptions that most criminals were amenable to treatment, or that treatments ever would exist, were questioned.24 Fourth, arguably too much discretion was vested in institutions that lacked the requisite authority or moral legitimacy. Said Judge Marvin Frankel: “The almost wholly unchecked and sweeping powers we give to judges in the fashioning of sentences are intolerable for a society that professes devotion to the rule of law.”25 Frankel doubted that judges and parole boards had the time or training needed to make meaningful sentencing decisions.26 More radical liberals condemned the system of indeterminate sentencing as a “tool of institutional control” that was used to perpetuate class and race biases by oppressing those who “challenge . . . the cultural norm.”27

Scholarly critiques of rehabilitation—and corollary support for retribution—abounded,28 and the critics were emboldened by research indicating that rehabilitation, did not, in fact, work. Sociologist Robert Martinson’s influential 1974 paper, What Works? Questions and Answers About Prison Reform,29 was widely relied on for its perceived conclusion that “nothing works” to reduce recidivism.30

Martinson himself later denounced the “nothing works” label attributed to his writings, and empirical research conducted by him and others in the late 1970s, 1980s and 1990s countered the pessimism regarding rehabilitative programs.31 Gradually, more and more scholars concluded that flawed methodology—and not flaws in rehabilitative programs—was largely responsible for their poor reported results.32

But by that point, the political tides had already turned.33 The framework of indeterminate sentencing was rapidly dismantled. By 1983, every state but Wisconsin had adopted mandatory minimum sentencing laws.34 In 1984, Congress passed the Sentencing Reform Act, which eliminated parole and established a complex system of determinate or presumptive sentences.35 Congress and many state legislatures also provided for harsher penalties in a number of other ways. They imposed life sentences for a variety of crimes, and created sentence enhancement provisions such as three-strikes laws.36 They made it easier to try and sentence juveniles as adults.37 They also reduced resources available for programs to rehabilitate prisoners.38 The “war on drugs” also led to an increase in resources allocated to criminalizing a pervasive social problem, and fewer resources dedicated to counteracting it.39

The combination of these factors has led to a ballooning prison population. Between 1925 and 1972, the national prison population remained fairly stable.40 But between 1972 and 1997, the number of state and federal inmates rose from 196,000 to 1,159,000—a nearly sixfold increase.41 In the next decade, the number behind bars nearly doubled again, and now exceeds two million.42 Our rate of incarceration—approximately one out of every 150 Americans—is the highest in the Western world by at least a factor of five, and has even surpassed the world’s previous leader, Russia.43 It is estimated that the United States has a quarter of the entire world’s prison population.44

The explosion of the prison population has also meant an explosion in prisons and prison costs. Between 1985 and 1995, the federal and state governments opened an average of one new prison per week.45 Between 1982 and 1993, government spending on corrections increased over 250%, far outstripping inflation.46 The rate of spending on prisons also grew to exceed spending on other social services.47 For example, in 1991, the federal government spent $26.2 billion on corrections to deal with 1.1 million prisoners and about five million probationers; at the same time, it spent only $22.9 billion on its main welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, which serviced 13.5 million people.48 Critics argue that spending billions of dollars on prisons diverts funds from social services that might prevent crime, and is thus counterproductive.49

As would be expected given the retributivist mood, the growth of prisons was accompanied by a reduction in resources and programming for rehabilitation. (Amenities not directly related to rehabilitation have also been scaled back considerably.)50 In 1994, Congress eliminated higher education grants for state and federal prisoners.51 Following this, at least half the states reduced prisoner vocational and technical training programs.52 By 2002, only nine percent of inmates were enrolled in full time job training or education programs.53 In 1991, then-governor of Massachusetts William Weld put it succinctly: “[inmates] are in prison to be punished, not to receive free education.”54 Some scholars have echoed this sentiment.55 What seldom gets asked is whether the savings in crime reduction resulting from educating inmates offsets the costs of the “free education.”

Nor is this trend away from investing in rehabilitation likely to change. Government prisons face political pressures against allocating resources to rehabilitation, and private prisons not only find expenditures on rehabilitation programs (or any non-essential programs) unprofitable, but may have a perverse incentive not to rehabilitate, since it would decrease the demand for prisons.56

Despite the growth of prisons and the worsening of prison conditions, the public still believes not enough is being done to be “tough on crime.”57 In a poll conducted in 1996, 67% of Americans thought that “too little” money was being spent on stopping “the rising crime rate,”58 and 78% said that the courts in their area treated criminals “not harshly enough.”59 Another poll conducted in 1996 found that 75% of Americans favored the death penalty—twice as many as supported it in 1965.60

This obsession with cracking down on crime exists despite empirical evidence both that crime rates are not that high,61 and that “tough on crime” policies are not responsible for making them lower.62 Our overall crime rates are not that different from other Western countries, undercutting the argument that we need more prisons because we have more criminals to deal with.63 Similarly, although it was widely believed that “zero tolerance” policing implemented in New York City in 1993, and the Three Strikes Laws adopted in California in 1994, were the reasons for their declining crime rates, violent crime rates were already beginning to decline in those locales in 1990 and 1991. Moreover, crime rates declined by similar amounts during the same period in places that did not adopt or enforce such policies.64 There is no general demonstrable connection between increasing the severity of criminal penalties and the reduction in overall crime rates.65

In fact, just the opposite is true: the evidence indicates that incarceration actually increases crime. A 1989 California study matched comparable felons sentenced to either prison or probation, and found that seventy-two percent of the former group was rearrested within three years of release, compared to sixty-three percent of the latter.66 Likewise, recidivism rates in a New York juvenile detention center were ten to twenty percentage points higher than those observed in a community-based alternative-to-detention program.67 A federal study drew the same conclusion: each instance of incarceration rendered the next more likely.68

The correlation between the ideological shift toward retribution and incapacitation, and the increased reliance upon—and worsening conditions within—prisons, is no coincidence. If criminals are monsters who are either undeserving of help or are by nature incapable of reform, it is sensible to lock them up and throw away the key. By contrast, we will see that Jewish law neither views criminals as monsters, nor treats them that way.

II. The Limited Role of Retribution in Jewish Law

Challenging the Popular Linkage of Retribution with the Hebrew Bible

As discussed above, those who favor prisons often invoke retribution as a justificatory rationale.69 And advocates of retribution often claim that the Hebrew Bible supports their position.70 Is their reliance justified?

At first glance, it would seem so. The phrase people most often associate with retribution is likely “an eye for an eye,” which appears several times in the Torah.71 Prosecutors (particularly in the heavily religious South) have often used it in closing arguments to induce juries to return the harshest possible verdict: the death penalty.72 In large part because of the prominent use of this phrase, the very term “Old Testament justice” is popularly understood to mean harsh vengeance.73 Legal scholarship, both liberal and conservative, also perpetuates this understanding.74 So do the media and the public.75 The Old Testament’s “eye for an eye” is often contrasted with the “turn-the-other-cheek” compassion and benevolence of the New Testament.

But how does one determine what the phrase “eye for an eye” really means? This is not unlike the situation one faces whenever engaging in statutory construction. Should one hew closely to the “plain meaning” of the text—which here suggests literal like-kind retaliation? Or should one look to the legislative history (whatever that would mean in the context of theocratic law) or other extrinsic evidence to aid in interpretation?

This Article asserts that because the society in which the Hebrew Bible originated, and for whom it was originally intended, looked outside the text’s “plain meaning” to discern what the law “was,” so should we. Although one might counter that any such “original” interpretation is not conclusive or binding on our understanding of the Bible today, only the most ardent post-modernist would contend that it is irrelevant.

- Issues in Interpreting the Hebrew Bible Generally

According to Jewish tradition, Moses received the Torah—the first five books of the Hebrew Bible76—from G-d at Mount Sinai in 1313 B.C.E.77 Although many are familiar with this claim, fewer are aware that the Jewish tradition holds that Moses also received from G-d a more detailed Oral Law,78 which was then passed down from teacher to student for generations. Between about 200 and 500 C.E., major portions of this oral tradition were reduced to writing in what is now known as the Talmud.79

The relationship between the written Torah and the Oral Law is a rich and complex one. One might analogize the written Torah to a lecture outline, and the Oral Law to the lecture itself. The outline is a shorthand, not intended to be read—and perhaps not coherent if read—independent of the oral presentation. Indeed, if the Oral Law appears to contradict or vary from the written Torah, then, according to the traditional Jewish view, “it is the former that governs.”80 The Oral Law is not a secondary source whose purpose is to illuminate a primary text. It is the primary source.

That the Jewish tradition does not embrace a literal interpretation of the written Torah is not surprising, given that the Torah is not a text that lends itself to any “plain meaning.” First, the Torah is written in Hebrew, a language that inherently allows for ambiguities regarding sentence structure, verb conjugation, and so on.81 Second, the biblical variant of Hebrew contains additional ambiguities that are not present in modern Hebrew.82 Third, Torah scrolls are written with no punctuation or vowels; lack of punctuation can create opportunities for ambiguity in any language, but the meaning of Hebrew words is particularly prone to change depending on changes in vowelization.83

Thus, when one reads the Torah, one is necessarily accessing a highly ambiguous text. Unfortunately, translations of the Bible into other languages “often resolve rather than preserve ambiguities, and thus favor one interpretation over another.”84 The linguistic problem rapidly becomes a substantive one, because one cannot coherently understand either the philosophy of Jewish law or the dictates of Jewish practice—known as halacha (literally, “the way” or “path”)—without turning to the Oral Law.85

- Interpreting “An Eye for an Eye” in Jewish Law

These challenges to interpreting the Torah directly impact the modern (mis)interpretation of the phrase “eye for an eye.” As one prominent contemporary biblical scholar has stated: “Few are the verses of the Bible which have been so frequently and glaringly misunderstood.”86 In Jewish law, the phrase in fact refers to monetary compensation for the value of the lost eye (in terms of pain and suffering, medical bills, lost earnings, and mental suffering),87 not literal retributive maiming.88

The arguments supporting this monetary compensation interpretation are numerous and varied. First, note that the words “eye for an eye” are ambiguous enough to permit the inference of compensation. If one wanted to lay down a rule of literal maiming, as distinguished from compensation, one could have done so far more explicitly. This is precisely what was done in Hammurabi’s Code of ancient Babylonia:89

If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out. If he break another man’s bone, his bone shall be broken. . . . If he put out the eye of a man’s slave, or break the bone of a man’s slave, he shall pay one-half of its value.90

Second, the phrase first appears in a section of the Torah dealing exclusively with how victims of an injury are to be compensated by a tortfeasor.91 Third, the Torah often prioritizes making restitution to the victim over punishing the offender; putting out the eye of the wrongdoer does not benefit the victim in any tangible sense.92 Fourth, the only forms of judicially imposed corporal punishment provided for by the Torah are capital punishment and lashes, not maiming.93 Fifth, given how the “tachat” in “ayin tachat ayin” (the Hebrew for “eye for eye”) is used in other places in the Torah, the use of this word suggests compensation, not literal blinding.94 Sixth, the Talmud offers a number of additional textual and logical proofs, too detailed to examine here, directed specifically to show that “eye for an eye” requires only compensation.95

If the Torah does not literally demand an eye for an eye, why does it use language that implies it does? One explanation rests on the distinction between the punishment the offender deserves, and the punishment that courts are authorized to impose:

[I]n the Heavenly scales, the perpetrator deserves to lose his own eye—and for this reason he cannot find atonement for his sin merely by making the required monetary payments; he must also beg his victim’s forgiveness—but the human courts have no authority to do more than require the responsible party to make monetary restitution.96

Thus, “an eye for eye” is an instance where the “plain meaning” of the text of the Torah will lead one to the opposite conclusion from what the halacha actually mandates.

Even if a modern reader were not persuaded by these arguments, the fact remains that this is the understanding that the Torah’s primary audience—Torah observant Jews—always had of “eye for an eye.”97 Moreover, not only does no instance of exacting such physical retribution appear anywhere within the Hebrew Bible,98 but apparently “there is no instance in Jewish history of its literal application ever having been carried out.”. . .99

III. Incarceration in Jewish Law

So far, we have identified the link between retributivism and the increased reliance on prisons. We then challenged the link between the Jewish law and retribution. This Part now examines the role of prisons in Jewish law. It demonstrates that prisons are not a prominent feature in Jewish law, and that Jewish law’s alternatives to prison are designed to promote rehabilitation, restitution and atonement, not retribution.

A. Prison in Jewish Law

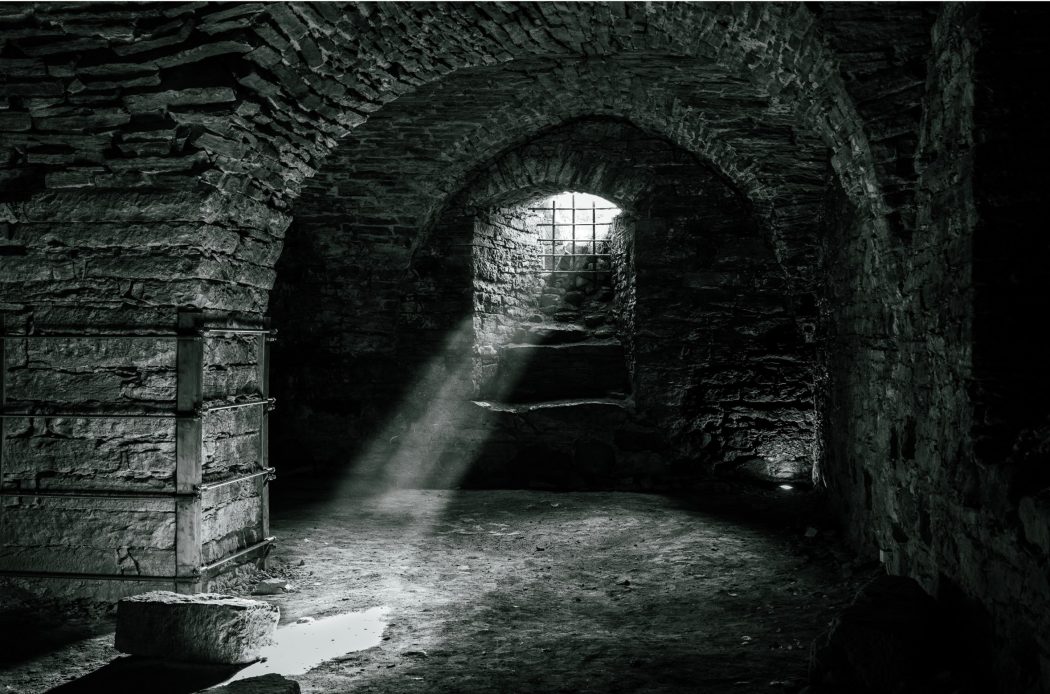

Jewish criminal law provided for a variety of forms of punishment—including capital punishment, flogging, fines, atonement offerings, and karet (spiritual death)—but prisons as we know them are “nowhere to be found in traditional Torah-based Jewish law.”100 This is not to say that there is no mention of prisons in the Hebrew Bible. But in the relatively rare instances in which they do appear, they are either not sanctioned by Jewish law, serve some function other than as a modality of punishment, or are tolerated as a second-best alternative to other forms of punishment.

- Prisons Not Sanctioned by Jewish Law

The narratives of the Hebrew Bible relate a few isolated instances where people are placed in prisons as a punishment for alleged crimes. When Joseph, after having been sold into slavery to the Egyptians, spurned the advances of his wife’s master, she falsely accused him of assaulting her, and he was imprisoned in Pharaoh’s dungeon.101 Likewise, when Jeremiah prophesized unfavorably, officers of the king, ostensibly because they suspected him of defecting to the Chaldeans, imprisoned him in a dungeon in one of the officer’s homes.102 Neither of these instances, however, shows that Jewish law endorses imprisonment. Joseph was imprisoned by Egypt, a non-Jewish society,103 and Jeremiah was imprisoned without trial, without factual basis, and in contravention of Jewish judicial procedure. Thus, the mere fact that Bible narratives refer to prisons does not mean that Jewish law sanctioned their use.

- Prison as a Means to Enforce Other Punishments

Incarceration was used in Jewish law to detain the accused pending trial or a convicted defendant pending sentencing. Where a potentially capital crime was committed, the offender could be imprisoned until the court could determine if a case could be made, or which form of penalty was appropriate.104 Although this pre-trial or pre-sentencing detention served to incapacitate, its purpose was not to punish, but to detain the offender until an appropriate punishment could be determined.105

Prison also served as a civil coercion mechanism. Imprisonment could be used as a method to compel compliance with a court order to divorce a woman to whom it was impermissible to marry,106 or, according to some sources, to pay a debt.107 Here, again, although coercive confinement served to inflict unpleasantness on the prisoner, the purpose of the imprisonment was not to punish him for criminal conduct, but rather to induce him to comply with a pre-existing court order which itself delineated the appropriate judicial response to his conduct.

In very limited circumstances, incarceration could be used as a means to carry out an execution. The Talmud108 discusses the case of someone who commits the same crime punishable by karet—premature death at the hands of G-d—three times. By willfully committing the same offense on three separate occasions,109 the offender has demonstrated that he has not repented, and in fact desires a premature death.110 After the third transgression, the offender is placed in a cramped cell precisely his height, so that there is no room to stretch out or lie down.111 He is fed scant amounts of bread and water so that his stomach shrinks, and he is then fed barley—which expands inside the stomach—until his stomach bursts and he dies.112 Similarly, one who kills another but is not liable to execution, either because of certain technicalities unrelated to his factual guilt,113 or because he is sophisticated in criminal laws and knows how to avoid liability—for example, by refusing to explicitly acknowledge the witnesses’ warning114—may also be subjected to this procedure.115

In both of these cases, the court is not authorized to execute the offender according to the halachic judicial formalities, yet it is clear that the offender deserves to die. Since the court cannot execute him directly, it uses incarceration to kill him indirectly. However, like the use of imprisonment as a means of compelling compliance with a court order to divorce or pay a debt, prison is used only as a means to carry out another penalty. Strapping the offender to a chair, bed, or wall, as opposed to confining him in a cell, and implementing the forced barley diet would have the same effect.

- Prison as a Lesser Alternative Punishment

Rambam, in his classic codification of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah, discusses several instances where prison may be used in lieu of a more serious punishment.

First, if the king declines to have a murderer killed (which he could do under his royal authority to protect the public welfare),116 he may nevertheless have him “beaten with severe blows—so that he is on the verge of death—imprisoned, deprived and afflicted with all types of discomfort . . . .”117 But this is weak evidence that Jewish law endorses prisons. The source for Rambam’s position is questionable— nothing in the Torah or the Oral Law itself mentions such authority. Perhaps since imprisonment is permitted as a lesser punishment where execution itself is already permitted, it is intended as a form of clemency.118 Moreover, Rambam is discussing the king’s authority to punish, which, as mentioned above, is independent of the courts’ authority to punish, and is not in accordance with the Sinaitic ideal of judicial procedure.119

Rambam also discusses a case where one or more murderers sentenced to execution become intermingled among one or more murderers who are not liable for execution, and those liable for execution cannot be identified. Rambam states that the entire group should be imprisoned, since all are potentially dangerous to society, and this contains that threat while avoiding the risk that an individual not subject to the death penalty is executed.120 But again, here prison is not the prescribed form of punishment for the crime; rather, it is a second-best alternative when individually tailored punishments are not practicable.121 Moreover, the factual scenario is so unusual that the ruling is not likely to have much practical application.

- Use of Prisons During the Diaspora

Some Jewish communities during the Diaspora—the period following the Roman expulsion of the Jews from Israel in 70 C.E.—did sanction a broader use of prison as a form of punishment than was prescribed under the Torah-based judicial criminal justice system. During this period, the Jews no longer had an autonomous government (at least until the establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948), and accordingly, a Torah-based judicial system could not be enforced. But a number of host countries did, to varying degrees, grant Jewish communities living within their borders a limited form of self-rule. Some of these communities permitted prison as a form of criminal punishment.

Two rationales were invoked to justify the use of prison in these circumstances. The first reason given was to deter crime and keep society safe, under the directive in Deuteronomy to “eradicate the evil from your midst”122 that applies above and apart from the enforcement of specific Torah criminal justice procedures. The second reason was to maintain good relations with the host society, under the dictate dina demalkuta dina (Aramaic for “the law of the land is the law”).123

But even in these circumstances, there were important Jewish authorities that refused to permit the use of prisons.124 Moreover, although the leaders who instituted these procedures may have been authorized to establish prisons, there was no disputing that this was a departure from the ideal.

Although prisons are not prominent in Jewish law, there are at least two notable examples of restrictive confinement in Jewish law. The first is cities of refuge, to which accidental killers would be sent. The second is involuntary servitude, which could be used as a penalty for theft. These alternatives to imprisonment reveal the Jewish view of the purposes of restrictive confinement. But a disclaimer is in order. Some of the specific practices regarding these punishments may seem incomprehensible or distasteful to the modern reader living in a secular society. I will attempt to explain, albeit superficially, the rationale behind some of these. But more importantly, the reader should remember that the purpose of discussing these Biblical punishments is not to advocate adoption of, or criticize the use of, particular details of the Biblical legal system. Rather, the purpose is to distill—even after having accounted for the cultural and historical differences—core principles still relevant in our time.

B. Cities of Refuge

- Which Killers Were Sent to Cities of Refuge

a. Homicide Classifications in Jewish Law

Much like modern law, Jewish law distinguishes between different grades of homicide, and provides for different punishments for each grade. The Torah distinguishes between intentional killers—who are liable to execution by the court125—and unintentional killers, who are not. It then further differentiates between three categories of unintentional killers.126

First is the inadvertent or negligent127 killer. He is exiled to a city of refuge128 in order to atone for the harm he has caused.129 The city of refuge serves as a haven for the negligent killer, and his time in exile provides him atonement.130 As long as he remains there, he is immune from retribution at the hands of the go-al ha’dam, or “blood redeemer”—usually the nearest relative of the slain victim.131 But if the killer is found outside the city of refuge, the blood redeemer may kill him without liability.132 Because leaving the city of refuge exposes the killer to the possibility of death, he is effectively confined there by threat, if not by physical restraints. Assuming a killer is judged liable to exile, he is required to remain in the city of refuge until the death of the Kohen Gadol, the High Priest.133 At this point, the slayer is deemed to have gained atonement and may return home.134 He is now considered an ordinary citizen, and if the blood redeemer kills him, the blood redeemer is liable to be executed.135

Second is the killer who acts “unintentionally [but] whose acts resemble those willfully perpetrated”136—i.e., who acts with gross negligence or recklessness.137 He is not liable to execution because he did not act intentionally; but his crime is too severe to be atoned for through exile in a city of refuge. Accordingly, he suffers no punishment at the hands of the court, and is subject to death at the hands of the blood redeemer wherever he finds him.138

Third is the killer “whose acts resemble those caused by forces beyond [his] control”—i.e., he acts with virtually no culpability because the killing is a freak accident that no amount of reasonable care could prevent. He is not punished at all. Because such a killer is deemed not liable, if the blood redeemer slays him he is liable for execution, just as if he had executed any other innocent person.139

Thus, Jewish law essentially distinguishes between intentional, reckless, negligent, and non-culpable killings. Intentional killers are subject to the most severe penalty, execution. Reckless killers are considered highly culpable, albeit less culpable than intentional killers; they are subject to the risk of execution at the hands of the blood redeemer, but their death is not guaranteed, as it is with intentional killers. Negligent killers are not liable to death, so long as they submit to the punishment of exile in a city of refuge. And non-culpable killers are not liable for any criminal penalty whatsoever.

b. American Law Compared:

The Jewish law classification of homicides, of course, looks much like our own. Under a typical modern statutory scheme, intentional killings are considered murder, and are subject to the most severe penalties—the longest prison sentences or execution; reckless killings are also often considered to be murder, but may be treated somewhat less severely; unintentional but negligent homicides (often called involuntary manslaughter) may still be criminal, although the penalties are often much less harsh; and those whose culpability in causing death does not even rise to the level of negligence are not punished criminally at all.140

Jewish law, like American law, makes the level of culpability a significant factor in deciding what punishment is warranted. Jewish law recognized a dividing line between those who were beyond rehabilitating in this world, and who thus needed to die to achieve atonement, and those who could be reformed through some lesser means of punishment, such as exile in a city of refuge. It is also telling that the primary purpose of exile (the closest Biblical analog to the modern institution of prisons) was reformation of the soul (the closest religious analog to the modern concept of rehabilitation).

But there are noteworthy differences. In Jewish law, one who causes the death of another through ordinary negligence is exiled.141 But, in modern American law, something more than ordinary negligence—“gross negligence”—is usually required to trigger criminal liability.142 Furthermore, the ostensible purpose of sending the accidental killer to a city of refuge is atonement.143 If atonement is a religious concept akin to rehabilitation—the “correction” of the offender’s soul144—how can we say that someone who did not intentionally cause harm (indeed, did not even consciously disregarded a risk of harm) is in need of rehabilitation?145

Again, the rationale for punishing the negligent killer, and for viewing him as in need of atonement, can only be understood in the context of religious law. According to Jewish philosophy, there are no true accidents.146 The physical word is a manifestation of the spiritual world. An accidental mishap in the physical world necessarily reflects some disruption in the spiritual:

A person can only sin even accidentally if he can imagine himself being able to exist as separate from G-d. . . . [W]hoever is insensitive to the Divine Image in others must also lack any awareness of this attribute in himself and leads to the conclusion that the murderer must have lost the awareness of his own spirituality long before he confronted the situation that resulted in his crime.147

The “accidental” killer, although he did not consciously disregard a risk in the instant he caused the victim’s death, is still culpable because it is only by virtue of his sin that G-d would lead him to a situation where he would cause another’s death.148 It is the sin that led the killer to commit the “accident” for which he must atone.149

There is, of course, no analog to this in American law. Human actions are considered to be the result solely of humans’ will, not G-d’s. Accordingly, people are punished criminally based on the consequences they intend or on the risks they disregarded or should have regarded, not on their level of “sin.”

Another feature that defies comparison is the rule in Jewish law that a killer remains exiled until the death of the High Priest. There is no apparent connection between the lifespan of one individual and the appropriate duration of punishment of another. This rule, too, can only be understood on a spiritual level.150 One explanation for it is that since the High Priest causes the shechinah, or Divine Presence, to rest upon the land, and the killer removes the Divine Presence by shortening the lives of others, it would be unfitting for the killer to remain free while the High Priest lives.151 Other commentators state that the rule is actually a punishment for the High Priest himself. Since it was his duty to pray that Israel would not commit the sin of murder, inadvertent killings show he neglected that duty. Thus, the killers’ terms of exile were tied to the High Priest’s lifespan so that they would pray for his death, since he failed to prevent their victims’ death through his own prayer.152 While these explanations for the duration of the sentence may hold sway in a religious context, they could never serve as justifications in a secular society.

While it may be neither feasible nor desirable for our secular legal system to borrow from Jewish law’s rubric of how to measure offenders’ culpability, or how long to punish them, we can still learn lessons from the cities of refuge. Given that the primary goal of exile in the cities of refuge was reformation of the offender, we can examine the conditions of the cities of refuge to see how Jewish law viewed the best way to accomplish this goal.

2. Conditions in the Cities of Refuge

a. Fostering Exposure to Positive Influences

All cities of refuge were Levite cities—cities of priests.153 Given that the purpose of sending the manslayer to exile was reformation of the offender,154 cities of priests were an ideal environment for him:

The fact that he was responsible for the death of another person requires him to closely inspect his spiritual standing. . . . The [cities of refuge] not only provide physical protection from the avenger of blood but also serve as a spiritual rehabilitation center for the murderer.155

Not only were killers sent to live among priests, but the cities of refuge could not be dominated by a criminal population who drowned out the influence of the “good eggs.” Rather, killers could not make up a majority of the inhabitants.156 A city also could not serve as a city of refuge if it lacked elders157—distinguished leaders who could educate and serve as role models to the city’s residents.

Just as the presence of spiritual role models158 helps make the city of refuge a “spiritual rehabilitation center,” the presence of positive role models can help make American prisons function as rehabilitation centers as well. Most prisoners today lack such role models; they are exposed primarily to fellow criminals and to prison staff who are usually either indifferent or hostile to them.159 Studies have shown that, in the absence of close supervision by adult role models, juvenile corrections programs are not only ineffective, but actually serve to increase deviant behavior.160 Adults may not be as impressionable as juveniles, but whom they associate with cannot help but influence them.

b. Limiting Exposure to Negative Influences

The laws regarding who cannot go to a city of refuge also serve to make the time of confinement conducive to reformation.

Although all killers may flee to a city of refuge pending trial,161 once a trial has been conducted, only the negligent killer may return to the city of refuge:162 the intentional killer is executed, and the sin of the reckless killer is considered too severe to be atoned for by exile.163 The net result of these rules is to segregate killers according to their differing levels of mens rea. Negligent killers in a city of refuge might end up associating with other negligent killers who have been exiled there, but no one within this pool of negligent killers will associate with any intentional or reckless killers.

Empirical studies have confirmed the beneficial effect on recidivism rates of segregating less serious criminals from more serious ones. According to one study, low risk offenders “‘show a shift in procriminal attitudes and behavior upon exposure to higher-risk offenders in institutions.’ Low-risk offenders placed in institutions ended up with higher re-incarceration rates than similar low-risk offenders who were placed in halfway houses.”164 John Martinson, the author of the study originally cited by retributivists for the view that “nothing works” when it comes to rehabilitation, later refined his position and argued that the success of rehabilitative programs depends on distinguishing offenders who are amenable to rehabilitation from those who are not.165 Jewish law was already making such distinctions at least two thousand years ago.

c. Humane Environment

Not only was a manslayer’s exile designed so that the people he encountered would facilitate his rehabilitation, but the physical surroundings themselves helped maintain a sense of dignity and foster his spiritual growth. Cities of refuge were required to possess all the basic needs for the slayer,166 including a source of water and marketplaces for provisions.167 If a city of refuge did not have a natural water supply, it was a public responsibility to provide it with one.168 The trading of weapons, or of activity that might lead to the introduction of weapons, was forbidden.169

In our prisons, by contrast, prisoners often face degrading living conditions. Overcrowding and a general atmosphere of brutality both between inmates and staff and among inmates prevail.170 These conditions create stress, fear, and anger, promote anti-social and violent behavior,171 and inhibit what potential for rehabilitation might otherwise exist.172 According to Michel Foucault, given the isolation, boredom, and violence, “the prison cannot fail to produce delinquents.”173 Even scholars who identify positive deterrent effects of unpleasant prison conditions acknowledge that these benefits may be more than offset by the dehumanizing environs’ tendency to inhibit reassimilation of the offender into society.174

d. Facilitating Community Reintegration and Identity-Building

Although the manslayer was removed from his former community, he was not isolated from the community within the city of refuge itself. Consider the following fascinating rule:

When a killer was exiled to a city of refuge, and the inhabitants of the city desire to show him honor, he should tell them, “I am a killer.” If they say, “[We desire to honor you] regardless,” he may accept the honor from them.175

This suggests several things. First, the inhabitants of the city of refuge could interact with the manslayer such that they would be aware of his conduct. Second, the manslayer could be engaged in socially beneficial activity—useful work, charitable deeds, etc.—for which the residents would wish to honor him. Third, he would have to state that he was a killer, indicating that the inhabitants may not otherwise have known that fact; he is not necessarily “branded” as a killer during his confinement. Fourth, even his status as a killer would not necessarily result in total ostracization, as the inhabitants might choose to honor him despite knowing that he has killed.

The possibility that a criminal might not only overcome the stigma of his crime, but even be recognized for distinction, is an important factor in his rehabilitation. “Most important for controlling crime . . . is that shameful expressions of disapproval of criminal or deviant acts be ‘followed by efforts to reintegrate the offender back into the community of law-abiding or respectable citizens . . . .”’176

Our prison system often does precisely the opposite. Prisoners are given few opportunities to earn the respect of the outside community, because they rarely interact with it. This is understandable, given the security risks. But given that most prisoners—especially those convicted of less serious crimes—will be returning to society sooner or later,177 the risk may be worth it. If re-exposing them to elements of the outside world makes them less likely to re-offend upon release, it may reduce the overall threat the prisoner presents to society.178

Indeed, many of today’s prisoners are not only deprived of opportunities for distinction, but every effort is made to make them literally indistinguishable:

Prisons are . . . institutions of depersonalization and dehumanization. This is due to the prisons’ emphasis on uniformity . . . . Life inside the penitentiary is very routine and can be numbingly monotonous. Prisoners are known as often by their numbers as by their names. Commonly adopted expressions of individuality such as dress and hairstyles . . . are limited . . . .179

By destroying their sense of self-identity, prisons make it that much more difficult for inmates to develop the strength of character to resist the pressures to reoffend when, as is usually the case, they return to society.180 Although there are valid security and prison management reasons for the totalitarian approach, there are alternatives. Delaware, for example, has enjoyed great success reducing recidivism of drug offenders181 by using their time in prison to reintegrate them through “therapeutic communities,” which are focused not merely on addiction but on a holistic approach to identity-building and social interaction. “The therapeutic community focuses upon the ‘resocialization’ of the individual and uses the program’s entire community, including staff and residents, as active components of treatment.”182 Similarly, one medium-security federal prison in Pennsylvania that adopted a philosophy of treating inmates humanely and incentivizing them to engage in pro-social behavior has yielded dramatic reductions in violence rates—while actually reducing administrative costs.183 Common sense suggests that using the period of incarceration as a “training ground” for coping upon release will yield more positive social behavior upon release.

e. Vocational Rehabilitation

The manslayer was to be gainfully employed within the city of refuge. The cities of refuge had to be larger than small villages, so that it would not be too difficult for a newcomer such as the slayer to earn a living.184 Obviously, there would be no concern with his ability to earn a living if it was not anticipated that he would do so. Similarly, although the manslayer need not pay his landlord rent in one of the six cities of refuge designated by Moses and Aaron, he would have to pay rent in any of the forty-two other Levite cities.185 The obligation to pay rent is a moot point unless he is gainfully employed.

Modern studies have shown that vocational training for inmates is crucial both to helping them develop the skills they will need to be productive citizens when they return to society, and to helping them develop the motivation to want to become such citizens in the first place.186 Unfortunately, this is what many modern American prisons are lacking, and such opportunities have grown even more scarce since the retribution movement has taken hold.187

f. Educational Rehabilitation

According to the Oral Law, if a Torah scholar commits manslaughter and is exiled to a city of refuge, his teacher is to go with him.188 Interpreting the passage in Deuteronomy that states that a manslayer shall flee to the city of refuge “and he shall live,”189 the rabbis concluded that “the life of one who possesses knowledge without Torah study is considered to be death.”190 Thus, the manslayer is not left to merely while away his time in exile in a meaningless existence. Indeed, not only is the offender’s education not interrupted by his confinement, his focus on learning can be that much more intense and concentrated while in the city of refuge.

Modern studies emphasize the importance of education during incarceration as an element of rehabilitation. Indeed, opportunities for social reintegration, vocational rehabilitation and education have all been cited as key components in some of the more empirically successful correctional and rehabilitative programs.191

Our society would not tolerate requiring a teacher who had committed no crime to accompany his student to prison. There are rationales for the rule: that the teacher himself needs to atone for some spiritual fault that must have somehow contributed to the offender’s killing;192 or that the teacher would be so absorbed in studying Torah that he would not mind leaving his community in order to continue his studies with his student. But these explanations do not make the rule palatable to us. Nevertheless, we must once again be careful not to ignore the important lesson regarding the importance of rehabilitation in punishment, even if we eschew the particular manifestation of the principle.

g. Shielding Offenders from Violence

The enforcement mechanism of the cities of refuge was not iron bars or electrified fences, but simply the knowledge that if the killer leaves the city, he may be slain by the blood redeemer. An obvious initial question is: why does the Torah sanction this form of seeming vigilante justice?

The simple answer is a practical one: the blood redeemer was a quasi-state agent. Ancient Israelite society had no formal police force, no corrections officers, and no court executioners.193 If a criminal defendant was sentenced to death by the court, the blood redeemer carried out the execution on the court’s behalf.194 That the blood redeemer was acting in an official capacity, and not merely to avenge a private wrong, is further evidenced by the fact that the Torah explicitly forbade the blood redeemer from accepting a ransom from the killer in lieu of his exile.195 Moreover, since the city of refuge was not designed to physically restrain the manslayer, and had no personnel designated to enforce his captivity, a credible threat of death upon leaving (like the revenge of the victim’s relative) may have been necessary to induce him to remain.196

But the blood redeemer did not go unchecked. Numerous protective measures minimized the chance that the blood redeemer would kill the slayer on his way to a city of refuge. This made sense, given that any killer traveling to a city of refuge was either seeking asylum pending trial (and thus the court had not yet decided whether he was liable to death); or else had already been sentenced to exile following a trial (and thus the court had affirmatively judged him not liable to death). To reduce the likelihood that someone not sentenced to die would be killed, the six original cities of refuge197 were spaced roughly equally throughout the land, so that no slayer would need to travel too far to reach any of them.198 In order to further facilitate rapid passage to the cities of refuge, the court was obligated to construct roads leading to each of them.199 The roads were to be twice as wide as regular roads.200 They were to be direct paths, without detours, and free of obstacles.201 The court was to inspect the roads annually and repair any defects.202 Signs stating “Refuge, Refuge,” were to be posted at intersections to ensure that slayers would know the proper path.203 Once the court adjudged a defendant liable to exile, he was escorted back to the city of refuge by two Torah sages, because they would have the wisdom to choose words that would calm down the blood redeemer, and because he would be reluctant to act violently out of respect for them.204

The slayer’s safety was further assured once inside the city of refuge. The blood redeemer was subject to execution if he killed the slayer within the city of refuge.205 Despite this prohibition, additional measures guarded against the risk that a blood redeemer might nevertheless try to attack the slayer within the city. Cities of refuge could not be large cities, such that the blood redeemer would have reason to frequent the place, and could blend in with the crowd while he sought his prey.206 They had to be near populated areas, and populous enough themselves, to defend against multiple blood redeemers should they attempt a mass attack on slayers within the city.207 Hunting and trapping were prohibited in the cities of refuge, since this could lead to the sale of weapons, which might be purchased by the blood redeemer. This ensured that, if the blood redeemer wanted to use a weapon within the city, he would be forced to bring his own, which would be detected upon his entry into the city gates.208

In the American penal system, victims’ relatives do not usually pose a threat to a convict’s physical safety (excluding perhaps participants in retaliatory gang warfare); but his fellow inmate often do.209 As Judge Frank Easterbrook succinctly put it, “Prisons are dangerous places.”210 Indeed, a quarter-century ago, the executive branch of the federal government conceded the dangerousness of prisons in a brief before the Supreme Court: “In light of prison conditions that even now prevail in the United States, it would be the rare inmate who could not convince himself that continued incarceration would be harmful to his health or safety.”211 Inmates also face the threat of sexual violence. Although accurate statistics on prison rape are difficult to obtain, given victims’ reluctance to self-identify,212 a 2001 Human Rights Watch report concluded that the problem was “much more pervasive than correctional authorities acknowledge.”213

Obviously, immersing offenders in violence does nothing to make them less violent when they return to society, and likely has the opposite effect. Moreover, if inmates must be at a constant state of attention to guard against assaults, they will have less time, attention, or willingness to devote themselves to more productive endeavors.

We have thus seen that the primary purpose of the cities of refuge was to provide atonement and rehabilitation for the slayer, and that its features were well suited toward promoting those goals.

C. Involuntary Servitude

- Servitude as a Sanctioned Form of Punishment in Jewish Law

The Torah provides that a thief is obligated to make restitution to his victim in the amount of the thing stolen, and in addition must pay a penalty (usually equal to the amount stolen).214 If the thief cannot pay the penalty, it becomes a debt he owes to his victim. But if he cannot pay the principal value of the goods stolen, he is sold as an eved—translated as “slave” or “servant”215—and lives in his master’s home for a period of six years.216 It was hoped that by dwelling in the home of a law-abiding family, the thief would learn from his master’s positive example, and reform his character so as not to steal in the future.217 Thus, the two primary purposes of this form of punishment were to make restitution to the victim and to rehabilitate the offender.218

The selling of a thief into slavery is a form of punishment only loosely related to prison. The eved or slave is not confined to a separate facility designated for the purpose of housing criminals, as prisoners are. Nevertheless, as a necessary incident of his obligation to serve his master, the thief’s right of unrestricted movement was abridged. Given that prisons were not generally employed under the Jewish criminal justice system, servitude, like the cities of refuge, is one of the closest analog to prison.

Of course, any proposal to “sell” someone into the service of another private individual would neither be embraced nor tolerated in the United States today. The very word “slavery” is, thankfully, anathema. However, the “slavery” into which the Jewish thief was sold was “more like indentured servitude for a term of years than slavery.”219 Not that one even needs to make this distinction in order to defend servitude as a mode of criminal punishment. The Thirteenth Amendment specifically permits the use of slavery and involuntary servitude “as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”220 Indeed, challenges to “chain gangs” and to other aspects of the post-Civil War plantation model of Southern prisons were sustained under the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, not on Thirteenth Amendment grounds.221 It is quite common for prisons today to require prisoners to do work in order to maintain the institution.222 Thus, the question is not whether it is permissible to punish criminals by requiring them to do work, but rather what type of work will it be, and under what conditions will it take place.

- The Relative Humaneness of Jewish Servitude

It is difficult to suggest that any form of servitude could be “humane.” Nevertheless, from a comparative standpoint, Jewish thieves sold into slavery were treated more humanely than many modern American prison inmates.

Jewish law explicitly acknowledged that the thief’s “self-image is depressed because of his being sold,”223 and accordingly imposed a variety of obligations on the owner designed to preserve his dignity. The thief was to be treated “as a hired laborer,” and could not be made to “perform debasing tasks that are relegated only for servants.”224 He was not to be made to perform tasks that were beyond his physical strength.225 His family was permitted to live with him, and although the master was obligated to provide for the sustenance of his slave’s wife and family, the master was not entitled to the proceeds of any work they performed.226

Although the slave was required to “conduct himself as a servant with regard to those tasks he performed,”227 the master was not allowed to hold himself above his eved:

A master is obligated to treat any Hebrew servant or maid servant as his equal with regard to food, drink, clothing and living quarters . . . . [The master] should not eat bread from fine flour while [the servant] eats bread from coarse flour. [The master] should not drink aged wine while [the servant] drinks fresh wine. [The master] should not sleep on cushions while [the servant] sleeps on straw.228 Indeed, the Sages suggested that the slave was to be treated as more than equal, saying: “Whoever purchases a Hebrew servant purchases a master for himself.”229

These myriad burdens that Jewish law places on the owner of a slave were intended to counteract the exploitative tendencies inherent in the relationship. They were designed to help ensure that the slave’s physical needs will be met, and that his psyche will not be unnecessarily damaged by his lowered status. In sheer economic terms, the legal requirements also make it expensive to be a slave owner, and thus discourage those who have neither the resources nor the inclination to treat a slave humanely from entering the slave-owning market.

By contrast, the incentive in modern American prisons is to house as many inmates as cheaply as possible.230 Not only is the prisoners’ dignity or psychological well-being not typically a priority, but one could imagine the public outcry if politicians and corrections officials devoted substantial resources or attention to those ends.231

- Seemingly Objectionable Aspects of Jewish Servitude

Despite the various ways in which Jewish servitude was preferable to modern American incarceration, some features of this form of punishment would seem illogical or downright unfair to the modern sensibility.232

First, we may object to letting the infliction of the punishment turn on the offender’s ability to pay. Only the thief who cannot repay the value of the goods stolen is sold.233 By making the imposition of servitude turn on whether the thief can repay the principal, Jewish law effectively makes the servitude a form of debtor’s prison.

One possible explanation is that Jewish law values restitution to the victim more highly than it values the criminal’s liberty. Another, more generous, explanation is that the servitude serves as a sort of welfare program. In Jewish law, there were two ways a Jew could become a slave. He could be sold into slavery by the court because of his theft, as has been discussed. Or, if he was severely destitute, he could voluntarily sell himself into slavery in order to raise funds to provide for himself and his family.234 It may be that the thief who cannot repay the principal of the amount he stole is so impoverished that he was in a position to sell himself voluntarily. Since he chose to steal rather than sell himself, the court forces an involuntary sale in order to raise funds both to repay the victim and to provide sustenance to the thief and his family. In this light, even the imposition of servitude is, albeit in a paternalistic sense, humane.

A second difficulty we encounter is accepting the possibility that anyone would be willing to have a convicted criminal—a thief, no less—serve his sentence by living and working in his home, with full access to all his possessions and in close proximity to his family. Such a possibility is only fathomable in a society very different from our own. The Sinaitic code was written for a “covenantal community”—a religiously homogenous society, all of whose members were motivated by a love of and a desire to serve G-d.235 Moreover, traditional Jewish culture has always been highly communitarian—interaction with other members of society is essential to fulfilling many of a Jew’s religious obligations.236 Thus, it is quite possible that a thief would not have come from a different culture and background, or even from a different neighborhood, than his victim. He may not have been the “other,” a presumed monster, as criminals today are usually perceived.237 Rather, he would have been a member of the victim’s own community who—even if he transgressed by committing theft—had quite a lot to lose by committing additional transgressions like stealing from his owner or assaulting the owner’s family. He also would not likely have escaped, as almost any modern convict undoubtedly would, because there was not really anywhere for him to escape to. As a member of the victim’s community, escape would be tantamount to self-imposed exile.

Third, Jewish law prescribed that the thief should serve as a slave for six years,238 regardless of the value of the articles he stole. The rationale for this rule was apparently that, since hired laborers would work for a term of three years, then a slave, who was essentially an involuntary hired laborer, should work twice that amount. Although it may seem unfair that a thief who stole a trifle and one who stole valuable goods would receive the same sentence, this is no worse than mandatory minimum sentencing schemes prevalent in today’s society. Thus, if it is unfair, it is unfair for the same reasons that modern law is unfair, not for reasons peculiar to Biblical law.

But the rationale for treating all instances of theft seriously, and for punishing them equally, was not a secular one. According to Jewish law, any theft was considered a serious crime—even more serious than robbery, even though the latter involves taking property by physical force. The reason for this is that the robber’s brazen act indicates that he fears neither man nor G-d, while the thief who steals in secret suggests that he fears men more than he fears G-d.239 Thus, even if petty theft was not a major threat to social stability or safety, it was a serious transgression in religious terms.

In any event, there were several ways in which a slave could secure his release prior to the six-year completion date. First, the slave went free if the master died without leaving a male descendant.240 Second, the slave went free if the Jubilee year (which occurred every fifty years) occurred during the term of his servitude, regardless how much time remained on his sentence.241 Third, the master could agree to accept the pro-rated value of the remaining services due him under the slave’s term, in lieu of receiving the services themselves.242 Fourth, the master could voluntarily manumit the slave and forgo a release payment altogether by executing a bill of release.243

Yet another aspect of Jewish servitude that evidences both its remarkable humaneness and it seeming unfairness simultaneously is the severance gift. Upon the completion of the thief’s term of servitude, the master was obligated to provide him with a generous gift of animals and/or produce—things that would perpetuate themselves and thus yield continuous benefit.244 This was to provide him with financial resources so that he could begin his life anew without the temptation to steal again.245 To ensure that the ex-slave would use the funds for the purpose of re-establishing himself, the law provided that his severance gift could not be expropriated from him246—a provision akin to a “spendthrift” trust for ex-convicts.

The mandatory severance gift is another rule that would never be accepted in our society. Millions of Americans who have committed no crime have difficulty providing for themselves and their families financially; the idea that released prisoners would be given a substantial endowment to begin their new lives (especially one paid for out of the public fisc) would cause an uproar.247

Nevertheless, the general principle that we should take concrete steps to help the criminal’s transition back into society and reduce the chances that he will reoffend is a sound one. Most convicts have no more money, education or training upon their release from prison than they did upon entering it. This, combined with the difficulty of finding employment due to the stigma of their ex-convict status, makes the temptation to fall back into criminal life considerable.248 Certainly the notion of facilitating the criminal’s reentry should be given consideration, given the costs of not doing so—higher recidivism rates, more crime, and the attendant added burdens on the police, prosecutors, and courts.

Thus, even aspects that at first seem strange or unjust may at their root be driven be humanitarian impulses. The difficultly, again, lies in translating these practices into measures that make sense in a different society and era.

Despite the challenges of translation, we can discern that Jewish law’s imposition of servitude as a penalty for theft stands as another example of a restriction on liberty that primarily served the goals of restitution and rehabilitation, not retribution. Moreover, given the goal of rehabilitation, the manner of punishment was designed to maintain the dignity of the offender and assist him in successfully reentering society. If players in the modern debate over the purposes and forms of punishment want to borrow a page from the Bible, it is these goals and ideas they should be looking to.

D. The Inconsistency Between Imprisonment and Jewish Law

It should come as no surprise that prison is not prominent in Jewish law,249 because incarceration conflicts with fundamental tenets of Judaism. According to Jewish philosophy, G-d created everything with a positive purpose.250 This includes every individual human being—even those who commit crimes—each of whose purpose is to love and serve G-d.251 According to this view, punishments for criminal transgressions should inure to the benefit of everyone involved—the criminal, the victim, and society at large. Prison is not a very good way to benefit any of these parties.

Prison is little help, and likely a hindrance, to the criminal fulfilling his purpose. Because imprisonment isolates the criminal, it undermines his ability to function in and contribute to society. And because serving G-d in Judaism is a highly social endeavor,252 the isolation that comes with imprisonment impedes his ability to serve G-d. Moreover, unless there is some aspect of the prison experience that facilitates atonement or rehabilitation, it does nothing to better the criminal. On the contrary, to the extent that prison serves to make criminals more likely to commit crimes in the future (as modern statistics suggest),253 it increases the chances that he will further sin, face additional imprisonment, and be further impeded in his ability to serve G-d. One could counter that we should not be concerned with whether the criminal is able to fulfill his purpose, that he has forfeited his right to do so by committing his crime. But this would be inconsistent with the Jewish worldview that it would have been worth creating the entire universe for any one individual254—whether he be a criminal or not.

The victims of crime are also usually not benefited much by isolating and confining the criminal.255 While imprisoned, it is highly unlikely that offenders will be able to engage in fruitful labor by which they can compensate victims or their relatives. Their incarceration does perhaps satisfy victims’ or their families’ desire for vengeance; but the drive for personal satisfaction through vengeance is generally not considered a legitimate interest according to Judaism.256 Moreover, since any form of enforced unpleasantness serves the goal of retribution, vengeance does not explain why prison should be the preferred method of inflicting pain over any other method.

As for society, imprisonment does provide a social benefit by incapacitating the criminal, although only so long as he is incarcerated. However, if prison makes criminals more likely to commit crimes in the future, this is obviously a detriment, not a benefit. Prison does potentially benefit society by deterring prisoners or others from committing crime, although the empirical evidence on this is questionable.257 In any event, the benefits to society of imprisonment must be weighed against its costs, and against the costs and benefits of alternatives. Studies suggest that alternatives to prison have had better success in reducing recidivism rates, and at a lower cost—in terms of direct outlays, not to mention the avoided costs of futures crimes committed by, and of the arrests, processing and confining of, would-be recidivists.258 Thus, the notion that prison is an institution that provides an overall benefit to society is questionable at best.

By contrast, Jewish law alternatives to prison serve, to the extent possible, to benefit the criminal, the victim and society.

As for criminals, spending time working and learning in a city of priests provides atonement and rehabilitation for the negligent killer. Similarly, the six years that a thief spends working in the home of a stable family gives him positive role models to emulate. And both punishments permit the offender to interact with society and to engage in productive work and study.

As for victims, having the negligent killer spend time in a city of refuge admittedly cannot benefit the dead; but then again, no punishment could ever directly benefit the victim of a homicide. At least as regards theft, however, the thief’s servitude does provide tangible restitution for his victim.

As for society, the threat of death at the hands of the blood redeemer keeps the negligent killer confined to the city of refuge, thus removing him from his native community. The thief’s involuntary servitude does not necessarily incapacitate him, although it is not clear how big of a concern incapacitation would be in his case. To the extent that these punishments only provide limited incapacitation benefits, this drawback may be more than offset by the reduction in recidivism that results from their strong emphasis on rehabilitation.

Thus, the punishments of Jewish criminal justice system are tailored to serve the purposes of that system. It is difficult to say the same of our own.

Conclusion

This Article does not suggest that we adopt specific punishments prescribed by Jewish law, such as cities of refuge or involuntary servitude. Jewish law is G-d-based law, written for a G-d-based society. Its punishments, and the rules for how to apply them, do not have practical application in a modern, secular society. (Indeed, it is not clear if they had practical application even in ancient Israel.) But the punishments in Jewish law evidence that system’s view of the appropriate purposes of punishment, and of the ways to advance those purposes. On that front, several core ideas stand out.

First, although there is a prevailing perception that Jewish law focused on retribution, our examination of the punishments that Jewish law instituted in lieu of incarceration reveals that rehabilitation and restitution were its priorities. To the extent that modern advocates of retribution invoke “Old Testament justice” to support the increased use of incarceration, they are relying on an incomplete and misleading view of Jewish law. If one wants to contend that the legal system embodied by the Hebrew Bible is so different from our own, in both its premises and operation, that no useful comparison whatsoever can be made of it, so be it. But if one does choose to examine it, one cannot deny that undue emphasis has been placed on the role of retribution.

Second, despite the possibility that Jewish law was not applied in practice, it embodied highly practical and sensible ideas about when rehabilitation was appropriate. Jewish law made a distinction between those criminals who were beyond rehabilitating in this world, and those that were not.259 For those whose crimes were so heinous there could be no atonement in this world, or who posed an intractable threat to society because of their repetition of serious crimes, Jewish law made incapacitation a priority, and authorized courts or the king to either execute them or possibly imprison them indefinitely.260 But lower level criminals—like negligent killers or thieves—would, in all likelihood, be returning to society. Both society and the offender would benefit from imposing punishments that improved these criminals’ chances for successful reentry into society. The punishments imposed by Jewish law reflected this fact.

Our current approach, by contrast, is to not only lock up the “lifers,” but to make more low-level criminal subject to imprisonment for longer periods of time, with little attention paid to what will happen to them once they get out. Thus, we may be giving up on far too many offenders, and doing far too little to help those on whom we are not giving up. Even if we were unwilling to do more to help prisoners for the prisoners’ sake, we should at least consider whether doing so is worthwhile for the sake of the protection of society. Given the fact that our current prisons make people more—not less— likely to commit crime, and given the ballooning costs of building and maintaining these prisons, it makes sense to look at legal systems that offer alternatives regarding how to deal with those offenders who will reenter society. In short, Jewish law shows us that we can prioritize rehabilitation without necessarily being “soft on crime.”

Third, even if the particular practices of Jewish law are impracticable in our own time, the policies underlying those practices are not. Cities of refuge incorporated notions of surrounding criminals with good influences and removing them from bad ones; of giving them a humane environment in which to serve their time; of allowing them to have community interaction and rebuild their identities following their wrongdoing; of giving them an opportunity to engage in productive work and to further their educations; and of protecting their physical safety so that these other goals could be achieved unimpeded. Similarly, the servitude imposed upon thieves was designed in such a way to ensure that the slave’s dignity was not needlessly impaired, and that he had both the psychological and practical wherewithal to avoid repeating his mistake.

We could not replace prisons with cities of refuge or private servitude, but we could adopt measures that embody the rehabilitative and restitutive principles on which those punishments were based. Measures such as increasing vocational and educational training, mentoring, and community service for prisoners, and increased reliance on intermediate forms of confinement for lower level offenders, may be a way of “translating” those Jewish law practices into our modern world.

The tenets on which the Jewish criminal system is based do not dictate that we scrap the prison system altogether. Jewish law seems to see some value in restrictive confinement. However, the value lies not in the fact of confinement itself, but in how we take advantage of that time to impact the person confined.